Opposition to HB 151 and HB 103

Representative John Carney

Representative John Carney

Committee on Education

702 Capitol Avenue, Annex Room 309

Frankfort, KY 40601

January 30, 2017

RE: Opposition to HB 151 and HB 103

Dear Mr. Carney,

I am writing out of a concern that these bills would reduce the existing JCPS school choice plan, resegregate schools, and take funds away from public schools.

I am a parent and a stakeholder in Jefferson County Public Schools. I also attended JCPS schools from kindergarten through high school. Frankly, I’m amazed at all the choices that are available in JCPS schools compared to what was available when I was a student. JCPS offers 18 magnet schools and 52 magnet programs at all levels. JCPS can tout several innovative programs. For example, the Academy at Shawnee offers programs in engineering, aerospace, and global logistics. Students can even earn a pilot’s license. Southern High School, one of five JCPS schools that is part of the Ford Next Generation Learning Initiative, offers programs in automotive technology, machine tool technology, business, and IT. Southern’s partnership with GLADA places students in internships. Additionally, the school has a Class Act Federal Credit Union run by students that provides students the opportunity to train and work in Class Act branches during the summer. Jeffersontown High School is participating in the Solar Car Challenge in partnership with Ford and the University of Kentucky. These are just a few examples from the high schools, as there are many more examples from elementary and middle schools.

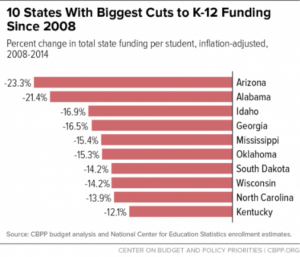

Moreover, JCPS has some of the top schools in the state and one-fourth of the state’s National Merit Scholars. In fact, JCPS students earned about $150 million in scholarships last year. All of this is especially impressive considering the fact that Kentucky has cut school funding to its public schools for the past several years. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Kentucky is one of 10 states with the biggest cuts to K-12 funding since 2008.

My concern is that these bills will threaten all the progress that JCPS schools have achieved and undermine public schools as a whole. The intent of HB 151 appears to be to allow students to automatically attend their neighborhood (resides) school. This bill would negatively impact the ability of JCPS to maintain the wide range of school choice options (e.g., magnet schools, career-themed high schools, and traditional schools) currently available to parents for their children. Most parents do not choose to send their children to their resides school. If this bill becomes a law, many students may not be able to return to their non-resides school that they currently attend because these schools would have to first offer all their available enrollment slots to resides students. And going forward, it would interfere with JCPS’ ability to offer school choice options.

More importantly, bills like HB 151 and HB 103 would lead us down the path of resegregating our schools. As a result, it would negatively impact equitable educational opportunities and student achievement. The gravity of this issue must be taken into consideration for any discussion of charter schools. In fact, the NAACP issued a statement in October 2016 calling for a moratorium on charter schools citing de facto segregation in the resolution. In their article on charter schools, Frankenberg & Siegel-Hawley caution that segregation in schools is still an important issue.

Segregation still matters because evidence consistently links racially and socioeconomically isolated schools to a variety of educational harms (see, e.g., Linn & Welner, 2007). For instance, students who attend minority segregated schools are far less likely to graduate from high school (Balfanz & Letgers, 2004), to experience high quality and challenging curriculum (Orfield, Siegel-Hawley & Kucsera, 2011) and to benefit from exposure to a stable, experienced, and highly qualified faculty (IDEA, 2007; Jackson, 2009). Each of these dimensions reinforces a cycle of low educational attainment for student groups who are poised to become the racial majority in this country. Meanwhile, white students isolated in overwhelmingly white schools do not learn to work and live with students from different backgrounds, an essential set of skills in an increasingly diverse and interconnected global society. (Frankenberg & Siegel-Hawley, 2012)

JCPS has had a long-standing community commitment to diversity and has been recognized for its efforts to desegregate schools. Here is some impressive proof from a report done by The Century Foundation:

The results of Louisville’s integration efforts are astounding. The average demographic for schools in the county is 49 percent white, 37 percent black, and 14 percent Latino and other ethnic and racial groups. Furthermore, among the largest twenty-five schools in the county, only one had more than 70 percent of the student body from a single race. As demonstrated in The Century Foundation’s recent report on the benefits of school integration, integrated schools such as Jefferson County schools also “prepare students for life, work, and leadership in a more global economy by fostering leaders who are creative, collaborative, and able to navigate deftly in dynamic, multicultural environments.” This is important, given that employers are overwhelmingly seeking those who can work with a diverse group of people. (Quick & Damante, 2016)

The bottom line is that integrated schools benefit all children. Diverse environments promote creativity, motivation, deeper learning, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills. As a parent, I want my children to be in a diverse school environment because they will be better off for it. Research shows that racial and socioeconomic diversity in schools provides students cognitive and social benefits.

School integration can be one way to combat institutionalized racism: there has been evidence that integration improves education for both white students and racial minorities; it can reduce the racial student achievement gap and allow black students to attend schools with better resources. And improved educational outcomes are crucial steps to increased political empowerment and expanded economic opportunities for children of color. With these overwhelmingly positive effects in mind, the percentage of people in favor of general integration has increased steadily over time, with 95 percent of the population in favor of blacks and whites attending the same school in 2007. (Quick & Damante, 2016)

Another chief concern I have is that this legislation would take funds away from public schools. Given that charter schools choose the students they will accept, this leaves students that are more expensive to educate (e.g., low-income, special education, ELL students) behind in public schools making that loss of funding more severe for the public schools. Here is an illustration of this from Bethlehem Area School District in Pennsylvania:

The public school fund drain from charters

Pennsylvania requires districts to pay the charter school a per-pupil tuition fee based on how much the district spends on its own students. In Bethlehem’s case, its per-pupil charter tuition cost per general education student is $10,635.77 and $22, 886.44 per special education student. In addition, the charter school students receive transportation funding from the taxpayers for attending any charter school located in the district or within 10 miles of any district boundary. The argument that charter proponents make is that since the school is no longer educating the student, the per-pupil amount it sends to the charter represents real savings for the district. But anyone who understands school finance knows that assumption is ludicrous. If class size is reduced from 28 to 27, or even to 25, you still must retain the teacher and her salary remains the same. The school does not lose a principal, custodian, cafeteria server or school nurse, even when sizable numbers leave. You can’t lower the heat or turn off the lights because some students and their funding have left for charters. (Strauss, 2017)

Admittedly, much work still needs to be done to improve public schools in Louisville and across the state. I am cognizant of the fact that there are problems that need to be addressed with JCPS schools. However, charter schools are not a panacea. As you move forward with legislation, I urge you to take into consideration what research has suggested. In a report done by Educational Testing Service called “Poverty and Education: Finding the Way Forward,” education reform and its failure to address the issue of poverty is discussed.

Some strategies are offered here to better match programs and services to the needs of children and to ameliorate the strong links between child poverty and later outcomes. We focus on seven areas that are generally within the purview of education policymakers:

-

Increasing awareness of the incidence of poverty and its consequences

-

Equitably and adequately funding our schools

-

Broadening access to high-quality preschool

-

Reducing segregation and isolation

-

Adopting effective school practices

-

Recognizing the importance of a high-quality teacher workforce

-

Improving the measurement of poverty (Coley & Baker, 2013)

Our public schools need to be adequately funded—with that funding targeted at schools that need it most so they can provide at-risk children social services and after-school programs. At-risk children in Kentucky also need access to high-quality preschool in order to prepare them for school. Finally, if you want to encourage innovation in the classroom, then public schools must move away from high-stakes testing.

Sincerely,

Deanna Ferreira

Louisville

Notes

Statement Regarding the NAACP’s Resolution on a Moratorium on Charter Schools. (2016, October 15). Retrieved from http://www.naacp.org/latest/statement-regarding-naacps-resolution-moratorium-charter-schools/

Coley, R. J., & Baker, B. (2013). Poverty and Education: Finding the Way Forward. Retrieved from https://www.ets.org/research/policy_research_reports/publications/report/2013/jqkw

Leachman, M., Albares, N., Masterson, K., & Wallace, M. (2015, December 18). Which States Have Cut K-12 Funding the Most? Retrieved from http://www.cbpp.org/blog/which-states-have-cut-k-12-funding-the-most

Quick, K., & Damante, R. (2016, September 15). Louisville, Kentucky: A Reflection on School Integration. Retrieved from https://tcf.org/content/report/louisville-kentucky-reflection-school-integration/

Siegel-Hawley, G., & Frankenberg, E. (2012). Not just urban policy: Suburbs, segregation, and charter schools. Journal of Scholarship & Practice. Retrieved from http://www.aasa.org/uploadedFiles/Publications/Journals/AASA_Journal_of_Scholarship_and_Practice/Winter2012.FINAL.pdf#page=3

Strauss, V. (2017, January 9). A disturbing look at how charter schools are hurting a traditional school district. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2017/01/09/a-disturbing-look-at-how-charter-schools-are-hurting-a-traditional-school-district/?utm_term=.0cbf32e79840